Course accuracy: why your GPS watch isn’t infallible

There’s something that is guaranteed to come up on every finish line of every race. No, not vomit – but course accuracy. These days, lots of runners have GPS watches, and it’s easy to imagine that they offer infallible evidence that the course measurer should be made to give you a piggyback to the finish line.

Of course, certified courses are always long, by one metre per kilometre – basically, to make sure that they are definitely not short. A car speedometer is the same – it errs on the side of caution so that it doesn’t inadvertently fool you into speeding.

Learning not to overly rely on your GPS when you are hoping to sneak a PB is an uncomfortable rite of passage for runners. I have done it myself and seen my goal time come and go, while the finish is still an agonising hundred yards away.

But let’s not be too harsh on GPS technology. It’s pretty epic, and it is incredibly useful for runners. Twenty thousand kilometres above your shoes, there are a bunch of about 30 GPS satellites in the sky. They are spread out, so that wherever you are on Earth, the sky above you contains at least four of them – and they pump out regular messages saying exactly where they are.

Your watch picks up these messages, and by looking at the time they were sent, can work out how far the messages have travelled. A satellite lurking over Manchester, say, might send a message that my watch receives 0.001 seconds later (light travels at 186,000 miles per second – take that, Usain!), so my watch can work out that I must be 186 miles from Manchester.

That’s not much use by itself; there are lots of places that are 186 miles from Manchester. But at the same time, my clever watch is collecting messages confirming that it is 53 miles from London, and 175 miles from Bognor Regis. Draw those three circles on a map, and they will intersect like an enormous Venn diagram, with you standing right in the middle.

Amazingly, this all happens in a device smaller than a matchbox, and it can pinpoint you to within 10 metres, over and over again. It can go a bit wrong if the messages bump into buildings or if the atmosphere is particularly soupy but, generally speaking, it is almost indistinguishable from magic.

So why is there a problem?

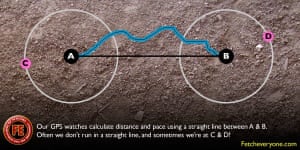

When I am in my happy place, nine-minute miling, I cover about 15 metres every five seconds. That’s how often some watches speak to the satellites to get a location. Here I am in the diagram, running from point A to point B:

And there is the first issue. Even if we assume that my watch is deadly accurate, and can pinpoint me exactly at A, and then at B five seconds later, it doesn’t know what I did in between. It calculates the direct distance between the two, but I might have run along the blue line to dodge a cowpat. GPS can underestimate how far I have run, and what I have trodden in.

But unless I take a real sharp bend, it is not going to be far off, right? Well yes, but if it misses out 50cm every five seconds, and I run for 45 minutes, that is a third of a mile missed; and my overall pace for the run would be out by 30 seconds a mile.

And we can’t rely on pinpoint accuracy either. The big circles around A and B represent the 10-metre error margin around each point. The watch could record me at points C and D – adding another 20 metres to the distance I covered in one five-second burst, turning nine-minute miling into Roger Bannister.

Luckily, though, your watch is just as likely to underestimate the distance between two points, which is why you often see your pace graph bobbling up and down on a consistent run.

As watches get more powerful, you can get around some of these problems by taking readings more frequently. My current watch takes a reading every second, so it captures more of my ducks and dodges; but that also means it has more potential to accidentally add a few metres on to my distance every so often.

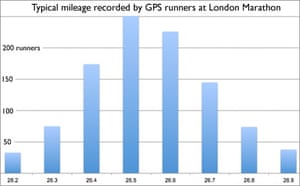

To see how these errors manifest themselves, you need to go big. I started by looking at the London Marathon. You know, the one on the telly. Our database holds more than 1,000 different GPS records for this one race alone, allowing me to build this histogram, showing the typical race distance recorded by London Marathon runners:

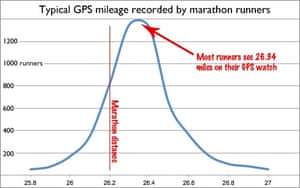

The most common distance is 26.5 miles, so either the ultra running community just got a million new members, or it confirms that GPS watches do plenty of overestimating in the busy high-rise tunnel-ridden dodge-and-weave bustle of London. But let’s be fair to London, and look at other marathons. Our database has 6,890 suitable GPS records at hand, and surely all those other marathons we keep hearing about will be bang on, right? Well, no.

The truth is that even if you follow the racing line, GPS data always contains errors. While the overall effect is not quite as pronounced as our London data, most runners will see a smidge more than 26.2 on their watches – a median figure of 26.34 miles. And though 0.14 miles isn’t especially far, it is an unwelcome treat when you have just run a marathon.

It is always worth keeping an eye on the mile markers during your race, particularly if you spot the ones that the course measurer has sprayed on to the ground. If they start to deviate from your watch, it could be a sign that your GPS is starting to wander. It gives you a chance to make small, relatively comfortable pace adjustments, rather than a panic in sight of the finish line. Above all, try to always make sure you hit the finishing straight with just a little bit of leeway. And if your GPS was spot on, enjoy that finish in style.

Ian Williams is the editor and developer of Fetcheveryone.com, a free website for runners. He loves this sort of thing, and writes a weekly newsletter which is sometimes as good as this.

Source: Read Full Article